A Perfect Summer Novel

Ferdinand-Hart-Nibbrig.-On-the-Dunes-in-Zandvoort-1891

Every year, I wait for summer to read a perfect romance novel. There is something about the ease of summer, the long evenings, and the abundance of time that makes reading a novel, especially a good romance, desirable. To me, a perfect romance novel must have everything: exceptional prose, a perfect setting, lively characters, engaging dialogue, philosophy, poetry, and beauty. Anything from “Brideshead Revisited,” “Remains of the Day” to “Franny and Zooey” falls under the great romance category for me.

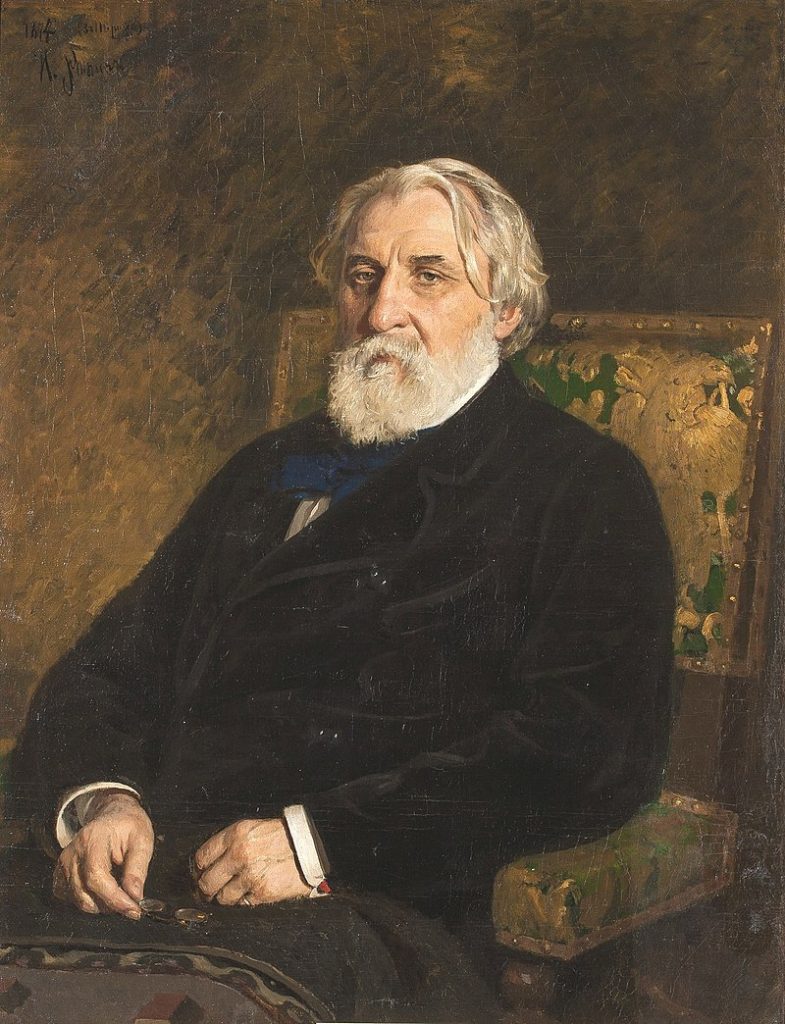

This year, a book that was on my reading list for a long time astounded me. “On The Eve” by Ivan Turgenev. I never assigned Turgenev’s figure to romance. Maybe it’s the grim look on his remaining portraits or the fact that so many great writers admire him or the Russian literature legacy that makes you expect dark and heavy text. Ernest Hemingway once said: “Turgenev to me is the greatest writer there ever was.” If you need encouragement to read Turgenev, this should be enough.

The story happens on the eve of the Crimean War in a Russian villa near the Moscow River where the Artemyevich family lives. A young and unhappy daughter, Yelena, lives with a despondent mother and an absent father who is apparently having an affair. There is also Shubin, a young man who is a distant family relation and has been in the custody of the Artemyevichs since he was a child. And then there is Bersenev, a friend of Shubin and a college student.

Turgenev has a way of describing his characters that’s so brilliant. For Yelena, he writes:

Weakness infuriated her, stupidity angered her, and a lie remained unforgiven by her “forever and ever.” Her demands yielded to nothing; her very prayers were not infrequently mingled with reproach. A person had only to lose her respect for her to pronounce judgment quickly, often too quickly, and that person ceased to exist as far as she was concerned. Every impression was sharply imprinted on her soul; life did not come easily for her.

She is the center of attention. The boys are in a rivalry for the love of Yelena. The novel opens with a chapter in which the two young male characters discuss philosophy and the meaning of love, beauty, and art.

Shubin, a college dropout and sculptor wannabe, has an intuitive approach to life and loves all things beautiful. Bersenev, on the other hand, is the top student at his university and, with his logical views, thinks love without empathy is not love, while Shubin, resembling Don Juan, declares that he only finds beauty in women. They start a fiery discussion on big questions in life like art, beauty, and happiness:

“Is it possible there’s nothing higher than happiness?” Bersenev said quietly.

“For example?” Shubin asked, then paused.

“Well, for example, you and I. As you say, we’re young, we’re fine fellows. Let’s assume each of us wants happiness for himself… but is this word happiness the sort of word to unite us, to enthuse us both, to compel us to join hands? Isn’t it an egotistical word? I mean, isn’t it a divisive word?”

“Do you know any words which unite people?”

“Yes, and there’s no shortage of them. You know them as well.”

“Really? What are these words?”

“Well, what about art since you’re an artist- ‘ motherland,’ ‘science,’ ‘freedom,’ ‘justice’?”

“And ‘love’?” Shubin asked.

“Love is also a word that unites; but not the love which you yearn for now: not love as pleasure but love as sacrifice.”

Then Insarov enters the picture, a revolutionary who yearns for freedom and dismisses any conservative ideas. A young man with ideals and a thirst for justice, with a tragic past. He is as poor as can be and has completely given himself to a great cause and has absolutely no place in her heart for a girl, which makes him a perfect object of desire. His broad shoulders and good looks aren’t much help either.

The novel also asks a bigger question: Will there be men among us? What Turgenev meant by this is probably a question of Russia at the time. The Russians were waiting for a real man in politics. Turgenev was worried about the morals of Russian society during his time. The Crimean War was primarily fought over control of the Holy Land, including Jerusalem, which was under Ottoman at the time. Russia sought to gain influence in the Ottoman Empire, which was in decline, and protect the rights of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman-controlled Holy Land. The Ottoman Empire, supported by France and the United Kingdom, opposed Russia’s expansionist ambitions and this led to Russia losing influence in the region.

Whom will Yelena choose to fall in love with? She is searching for a man of depth, principle, and strength of character who can provide moral guidance and lead the way forward. Elena’s quest for such a man reflects Turgenev’s broader concerns about the direction of Russian society.

She only teases Shubin, and she finds the learned and logical man, Bersenev, interesting. He can talk about philosophy for hours, and that fascinates Yelena, but then in a strange turn of events, when they are both alone, Bersenev starts talking about his noble friend, Insarov, who is not Russian but speaks the language and wants to free his native land, Bulgaria. Too busy to impress Yelena, Bersenev doesn’t notice that he is praising the virtues of another man to her. Yelena is intrigued and wants to meet this incredible man, and soon she finds herself desperately in love with him.

Her family would not approve of him, so they decide to elope and go to Bulgaria to join the revolutionaries waiting for Insarov. But Insarov gets miserably sick and dies in Venice. Yelena is left alone and without love. The happiness she felt for a few moments in her life is now gone. She will not go back to her family and her past life although she could. Instead, she chooses to dedicate herself to a greater cause. She decides to go to Bulgaria and help the revolutionaries. Some say that they have seen a woman dressed in black attending to wounded soldiers. Others say the boat she was in drowned with no traces of her. I like to think she found peace in her remaining days or possibly a glimmer of happiness.

As for Turgenev’s question, “Will there be men among us?” Shubin asks a friend in a letter: “Remember, what you told me the night we learned of the marriage of poor Yelena, when I was sitting on your bed and talking to you. Remember I asked you then, ‘Will we have real people here?’ and you answered: ‘There will be… And now today, from my ‘beautiful afar,” I again ask you: ‘Well then, Uvar Ivanovich, will there be?” Uvar Ivanovich wagged his digits and gazed enigmatically into the distance.

I don’t think Turgenev was optimistic about it.