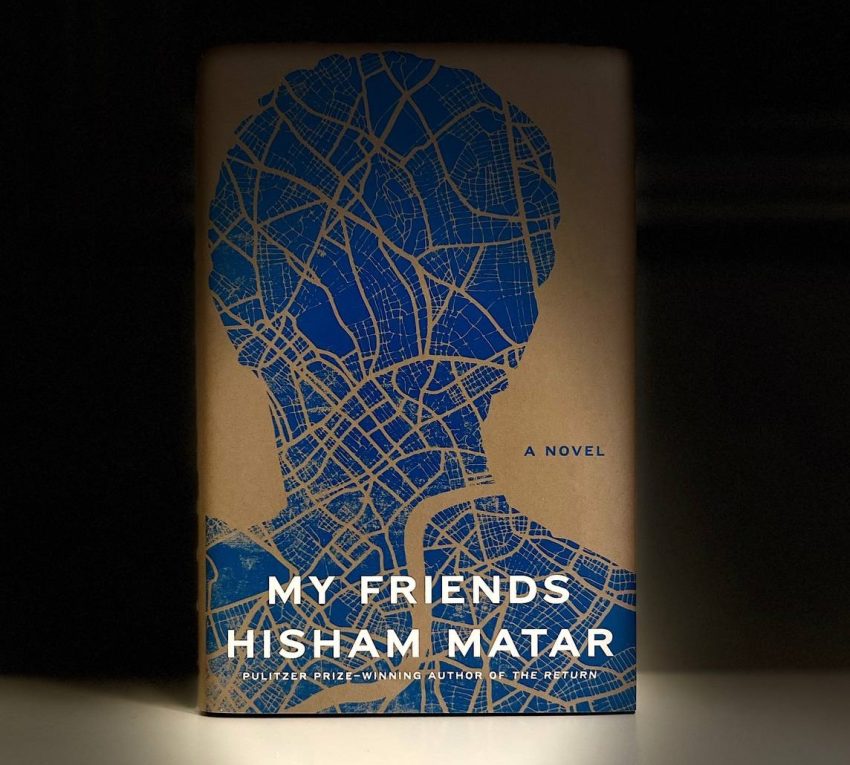

My Friends by Hisham Matar

The latest novel of Hisham Matar Published by Random House

Those who have been displaced, left their home, or lived in exile, know how hard it is to commit, not only to the new place but to anything that gives the illusion of stability or a permanent state of mind. Anything other than practical, cannot stay. You have to think before committing, even to a potted plant. You don’t know where your next destination will be, and even if you do, you secretly hope to return someday. And if books are an integral part of your life, imagine committing to a home library in exile.

My Friends, the latest novel of Hisham Matar is about three young Libyans who become exiles. One without any books, who believes in action rather than words. The one who is a writer with a small selection of books that he can carry and the protagonist of the novel, who has managed to build a small library in his flat in London. We follow their lives and the timeline of their friendship and the turn it takes after the Arab Spring and the fall of Ghaddafi, as we walk with Khaled, through the streets of London, over the course of a day.

Hisham Matar opens the novel “My Friends” with one long beautiful sentence:

“IT IS, OF COURSE, impossible to be certain of what is contained in anyone’s chest, least of all one’s own or those we know well, perhaps especially those we know best, but, as I stand here on the upper level of King’s Cross Station, from where I can monitor my old friend Hosam Zowa walking across the concourse, I feel I am seeing right into him, perceiving him more accurately than ever before, as though all along, during the two decades that we have known one another, our friendship has been a study and now, ironically, just after we have bid one another farewell, his portrait is finally coming into view. And perhaps this is the natural way of things, that when a friendship comes to an inexplicable end or wanes or simply dissolves into nothing, the change we experience at that moment seems inevitable, a destiny that was all along approaching, like someone walking toward us from a great distance, recognizable only when it is too late to turn away.”

In an interview, he mentioned that he’s been carrying this exact paragraph for about 10 years: who are these people and what are they trying to say? He’s been wanting to write about the Arab Spring and the Libyan embassy incident and was waiting for the right time. After writing several books, he finally managed to come back to this subject and published “My Friends” in 2024.

On April 17, 1984, a protest organized by Libyan dissidents took place outside the embassy in London. During the protest, shots were fired from within the embassy, resulting in injuries to several demonstrators and the death of Police Constable Yvonne Fletcher, who was stationed nearby. As a result, three friends, two of them wounded in this protest, cannot go back to the life they had. These young men start to improvise a new life in exile. The novel My Friends takes historical facts and puts them in conversations with fictional characters and it is so greatly put together that several times I had to fact-check online about the characters and events in the book.

How do you write about a real event in history that impacted you, how do you stay true to the heart of the event, without making it look like a documentary or simply a report? In a recent interview on CNN with Christiane Amanpour, Hisham Matar talks about the how: “In any revolution, people act on their temperament, where people end up isn’t always because their ideology and ethics and …It has something to do what I call temperament. Somebody’s personal taste and I thought the novel is a place for exploring this temperament.”

The novel starts with a farewell, where Khaled, the protagonist, is saying goodbye to a dear friend at Kings Cross station in London. Khaled decides to walk home and during this walk, he remembers and reviews the events that led to this day, the inevitable goodbye. He thinks about all these moments of joy, sadness, and hidden jealousies in this friendship. It reminds you of Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf in a way. Mrs. Dalloway is going out in London to buy flowers and we get to know all of her intimate thoughts as she goes about her day getting ready for her dinner party. Virginia Woolf’s name appears several times throughout the novel. Once, the protagonist faces an interview for admission to a literature program. During the interview, he is read a paragraph from Mrs. Dalloway. When asked about the author, he admits he doesn’t know, but he finds the writing beautiful. Or when the two friends decide to go on a pilgrimage in London and visit the writer’s former houses and end up at her house, “lingering at her doorsteps, as though we were expected”. The book is a homage to writers. Writers in exile and writers who lived in London, such as Virginia Woolf, Gene Rhys, Joseph Conrad, Ford Max Ford, Henry James, Ezra Pound, T.S. Elliot, Dambudzo Marcheba, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

The book is constructed with the attention of an architect. The writing is beautiful. Short chapters help the narration flow as if an invisible path is guiding you without noticing through time, then and now. London is alive and very present and talked about throughout the book:

“London, the city I have been trying to make home for the past three decades, thinks in certainties. It enjoys classifications. Here the line separating road from pavement, one individual from another, pretends to be as definite as a scientific fact. Even the shadows are allotted their places, and London is a city of shadows, a city made for shadows, for people like me who can be here a lifetime yet remain as invisible as ghosts.”

There is no sign of a missing father in this book, but the ideas of home, exile, and the desire to return are still present:

“Soon you will be home, Mother would say. She said it nearly every time we spoke, and each time I said yes, I believed I meant it and not just because I did not know how else to answer or how to account for the fact that, though Benghazi was the one place I longed for the most, it was also the place I most feared to return to. The life I have made for myself here is held together by a delicate balance. I must hold on to it with both hands. It is the only life I have now. I would have to abandon it to go back, and, although I wish to abandon it, I fear I might not be able to reconstitute a new life, even if that would be in the folds of the old one. It is a myth that you can return, and a myth also that being uprooted once makes you better at doing it again.”

One cannot help but wonder if these thoughts also occupied the author’s mind about returning. And if you are lucky to have read Hisham Matar before, it’s like walking in familiar corridors and rooms of Andrey Tarkovsky’s films and feeling the dreams and dispairs of a generation that disappeared into history.

*You can read more about Hisham Matar, here:

Leave a Reply