Reading Natalia Ginzburg

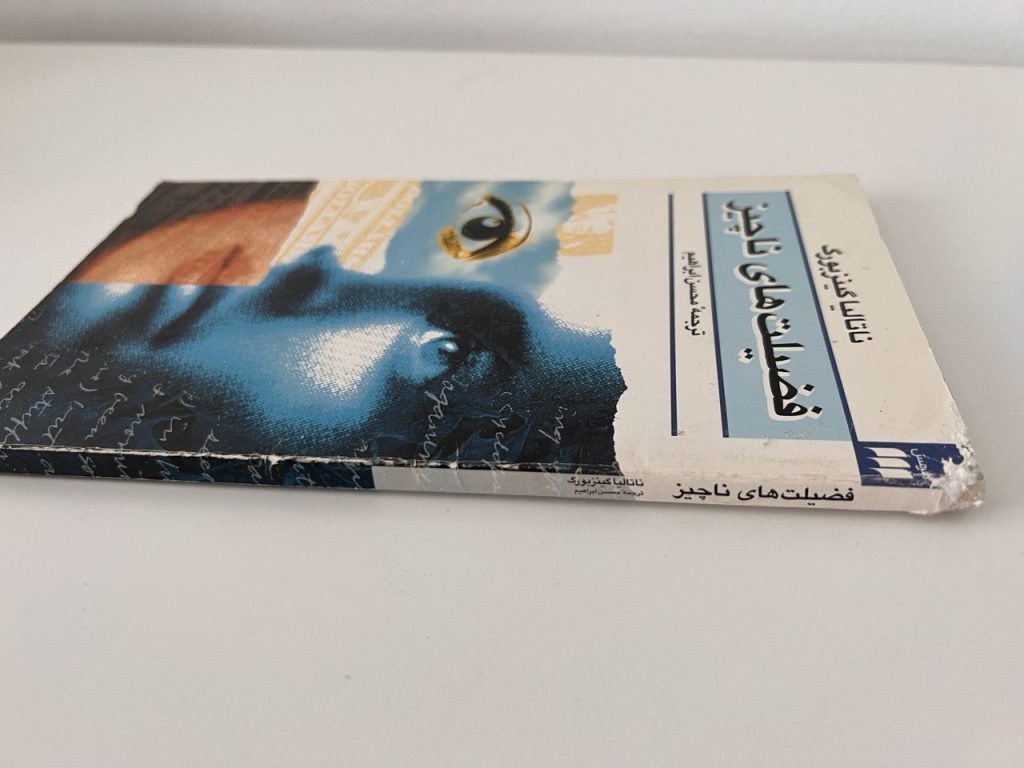

“This is a photograph of Natalia Ginzburg’s book, ‘The Little Virtues,’ in Persian, which I’ve carried with me over the years:

It’s my answer to the question of which book I would choose to take if our entire civilization were moving to Mars. The corners of the book, as you can see in this picture, are chewed. It was around the time when my son was teething and chewed his way through my library. Ironically, this was the book he liked most, probably because of its lightness and size. I secretly hoped that some of the wisdom in the book would transfer to his brain. In the uncertainty and fragility of motherhood, I believed I had everything I needed to conquer the hardship of raising another human being with what Natalia Ginzburg taught me.”

“As far as the education of children is concerned, I think they should be taught not the little virtues but the great ones. Not thrift, but generosity and an indifference to money; not caution, but courage and a contempt for danger; not shrewdness, but frankness and a love of truth; not diplomacy but love for one’s neighbor and self-denial; not a desire for success, but a desire to be and to know.”

I cannot agree more with Lisa Taddeo, the American author and journalist, who said:

“This entire book should be required reading for everyone who is born. You should receive a copy with your birth certificate.”

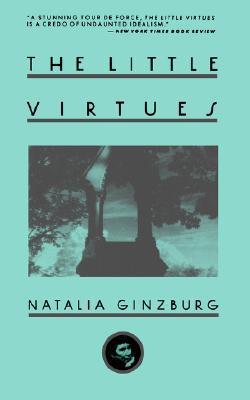

Natalia Ginzburg wrote The Little Virtues, Between 1944 and 1960. From the Italian countryside, where she and her husband lived in exile under fascist rule, to the melancholy streets of 1960s London, Ginzburg explores loneliness and belonging against the backdrop of post-war Europe. In The Little Virtues, Ginzburg takes familiar objects and experiences – worn-out shoes, money boxes, meatballs, childhood, silence – and transforms them into subjects of great significance. While haunted by the political events of the time, Ginzburg rests her gaze on the human intimacies that shape and define our lives: friendships, marriage and parenthood. She describes her longest relationship – with her writing – in a definitive piece on vocation:

“When I write something I usually think it is very important and that I am a very fine writer. I think this happens to everyone. But there is one corner of my mind in which I know very well what I am, which is a small, a very small writer. I swear I know it. But that doesn’t matter much to me. Only, I don’t want to think about names: I can see that if I am asked ‘a small writer like who?’ it would sadden me to think of the names of other small writers. I prefer to think that no one has ever been like me, however small, however much a mosquito or a flea of a writer I may be. The important thing is to be convinced that this really is your vocation, your profession, something you will do all your life.”

Her writing is plain but in the best way. The words are sterile and without any emotions, but when put together, they reach places in your heart, you didn’t know they existed.

Natalia Ginzburg wrote around 14 novels, numerous essays, and several plays, full of melancholic characters and lonely human beings, which she likes to explore. Men and women who feel alone with their feelings in the face of the world and the decisions they make and paths they choose make them even lonelier.

Her first published work was a novel titled “The Road to the City”, which was released in 1942. This novel marked the beginning of her literary career. Ginzburg’s marriage to Leone Ginzburg, the editor and journalist, who met his death at the hands of the Nazis for his anti-Fascist activities, and her work for the Einaudi publishing house placed her in the center of Italian political and cultural life. She was a member of the Italian Parliament for a brief period in the 1980s, representing the Italian Communist Party. In an interview with Marino Sinibaldi for Radio Tre Italy, she says :

“When I went into government, they said to me I shouldn’t go, my children especially. One of my sons said, “You’ll be bored out of your mind because you won’t understand anything.” And it’s true, I hardly ever understand anything, but I must say I don’t get bored. I may be sitting there thinking my own thoughts, but every now and then I’ll pick something up, which I take home and think about. Maybe I’ll write an article because I rarely give speeches.”

Her political involvement, however, was not the central focus of her career. Aside from a few political articles, Natalia Ginzburg is only interested in small ordinary life details. In the loneliness of people and the silence and gaps when they talk to one another. She is the observer of the human life. Only a handful of authors could achieve that, and Chekhov is one of them. Natalia Ginzburg was a great admirer of Chekhov. Ginzburg admired Chekhov’s keen observations of human behavior, his empathy for his characters, and his ability to convey the profound within the ordinary.

Natalia Ginzburg wrote her masterful autobiographical novel Family Lexicon or Family Sayings, while living in London in the 1960s. Homesick for her Italian family, she summoned them in this celebration of the routines and rituals, in-jokes and insults and, above all, the repeated sayings that make up every family.

‘The places, events and people are all real. I have invented nothing.’

Yet she manages to never talk about herself and her feelings. Natalia Ginzburg, always spoke of herself with irrepressible modesty, even when the most devastating thing happened. This is what she writes about the death of her young husband under torture by Nazis in her book, Family Lexicon:

“On the wall in his office the publisher had hung a portrait of Leone: his hat slightly at an angle, his eyeglasses low on his nose, his thick black hair, his deeply dimpled cheeks, his feminine hands. Leone had died in prison, in the German section of the Regina Coeli prison one icy February in Rome during the German occupation.”

In “Family Lexicon,” the characters all talk about their boring lives, and only when the horror of fascism happens do they begin to see it. Ginzburg always has the sensitivity for the little moments we feel in our hearts. In “Winter in Abruzzi,” she writes:

“My husband died in Rome, in the prison of Regina Coeli, a few months after we left the Abruzzi. Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish that preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow. At that time I believed in a simple and happy future, rich with hopes that were fulfilled, with experiences and plans that were shared. But that was the best time of my life, and only now that it has gone from me forever—only now do I realize it.”

Whether writing about the Turin of her childhood, the Abruzzi countryside where her family was interned during World War II, or contemporary Rome, Ginzburg never shied away from the traumas of history—even if she approached them only indirectly, through the mundane details and catastrophes of personal life. She is one of the finest writers of the twentieth century, and describing her work is almost impossible. I will never forget the first time I read her in Persian. Thanks to the brilliant translation by Mohsen Ebrahim and the kindness of a bookseller who took an interest in educating me when I was very young, I encountered her words, and they have hardly ever left me through the years.