Tahar Djaout: Defying Oppression Through Words

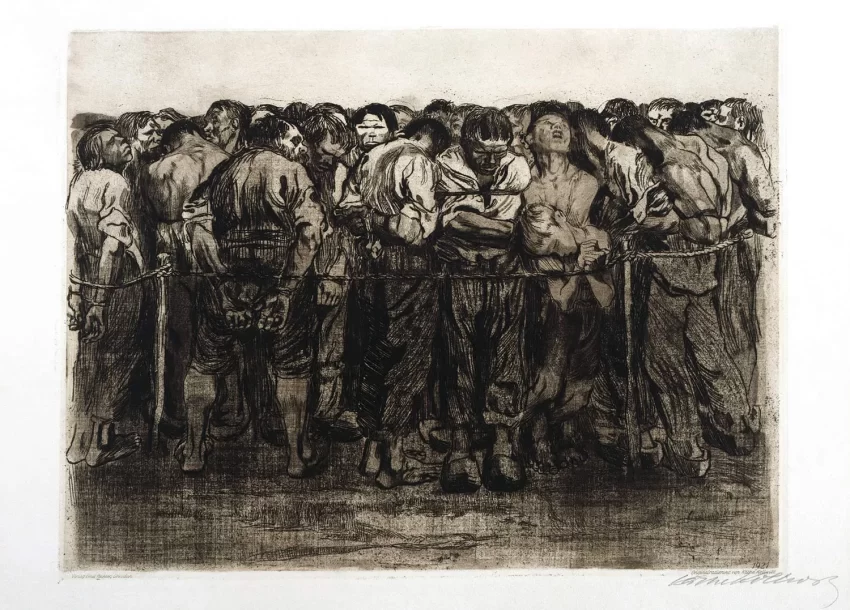

‘The Prisoners’ (‘Die Gefangenen’), (1908), Käthe Kollwitz. Source: Trivium Art History

Tahar Djaout ended his novel, The Last Summer of Reason with these words: Will there be another spring? Sadly, for him, there wasn’t. In 1993, Tahar Djaout’s life was tragically cut short when He was assassinated by the Armed Islamic Group because of his support of secularism and opposition to what he considered fanaticism. He was attacked as he was leaving his home in Algeria. By the time of his death, he was only thirty-nine years old. His death sent shockwaves throughout the literary community. The loss of Djaout was not just the silencing of an individual voice but a profound blow to the freedom of expression and intellectual progress in Algeria. The Last Summer of Reason, a novel he had been working on at the time of his murder, was published without alterations in 2001.

Reading Tahar Djaout’s slim and poetic novel is significant not only because the writer gave his life to pen these words, but also because it looks right into some of the most urgent issues of our time: book bans, censorship, and the harrowing experience of living under an extremist regime.

The protagonist in the novel, Boualem Yekker, is a bookseller who is in love with books:

Books — the closeness of them, their contact, their smell, and their contents — constitute the safest refuge against this world of horror. They are the most pleasant and the most subtle means of traveling to a more compassionate planet.

The presence of the books is essential to his being, to the measure that when they close his bookshop, he feels completely disoriented.

“He is like a plant that has been torn from the soil, separated from liquid and light, its two vital necessities. He has been excluded from the life of books. He has been exiled from all the landmarks of his childhood: values trampled, symbols corrupted, spaces disfigured and wrecked.”

Boualem is one of the few who has not yet been brainwashed by the oppressive system. He receives death threats and even gets stoned by local children. Shockingly, one day he discovers his own child has turned into one of the Vigilant Brothers and become part of the very system he opposes.

There is a scene in the book when Boualem receives a threatening call from anonymous callers when he is alone in his shop. The shrilling rings of the telephone and the terror he feels afterward are a clear picture of how an oppressive system invades your most intimate and quiet moments and can unsettle your spirit. Boualem is filled with rage but finds himself unable to act when the phone rings again. The fear and rage have made him paralyzed.

The Last Summer of Reason” unfolds the tale in a narrative style reminiscent of Kafka’s “The Trial.” In most reviews, the book has been described as a dystopian novel and often compared to George Orwell’s 1984 but reading it today, it feels more contemporary than it wants to be.

Tahar Djaout’s novel resonates deeply with current times, particularly these days, with reports emerging from Iran where certain bookshops are being forcibly shuttered and barricaded with cement blocks to stifle their operations. Superficial justifications are offered, such as the absence of a license or the non-compliance of female staff with compulsory hijab. Yet, everyone knows the true cause: the fear of a space known as a bookshop, a gathering point for intellectual and youthful minds to freely exchange thoughts and ideas. Even though most books sold in these establishments must pass the scrutiny of the so-called Ministry of Culture’s censorship test.

You would expect these measures in a country under a fundamentalist regime, but in today’s United States, the topic of book bans has become a contentious issue, sparking heated debates, and raising concerns about freedom of expression. While the concept of banning books is not a new phenomenon, recent events are a wake-up call for any society that values freedom.

As Hisham Matar mentions the “book ban culture” in his enlightening conversation on Podcast Noor:

“When books are banned, it’s a symptom of a bad time. All attacks against books usually have to do with power or somebody who wants to oppose its authority. Why is a dictatorship concerned about books? How many people read? Why put writers in prison? How dangerous a book can be? But the truth is, that it’s deeply dangerous. One of the remarkable things about a novel is that it can suspend authority. It’s not very clear where the power is. Novels are usually about contested spaces. They are enlivened by contradictions…if you want to impose an authoritative narrative whether as a dictator or some dogmatic extreme bureaucrat in some city in America banning books in school, this is the way.”

It’s astonishing how fundamentalists and extremists are acting the same everywhere in the world, even in a fictional place. In the first chapter of the book called Sermon 1, Tahar Djaout reflects on censorship:

“But is it all about ideology or religion? Or has it to do just as much with power and domination? Conformism is an elementary conditioning of society that is essential for the exercise of power, be the route one of the impositions of a secular or a theocratic ideology. The history of censorship is an old one, censorship not merely of the written word, but of the spoken, censorship in dress codes, human relationships, dietary choices, lifestyles, and even thought.”

The Last Summer of Reason adopts a third-person voice that follows the protagonist’s thoughts, dreams, and haunting nightmares, inviting readers to traverse the labyrinthine corridors of Yekker’s consciousness. He lives in a country obviously modeled on Algeria. Like Algeria in the early 1990s, the nameless country in the book is engulfed in turmoil and terror. Multi-party elections were held, with the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) gaining initial success. However, fearing the rise of an Islamist government, the Algerian military intervened, canceling the elections and sparking widespread unrest. This led to a civil war characterized by violence, terrorism, and human rights abuses. Islamist groups like the GIA and AIS clashed with government forces, causing a death toll of 100,000 to 200,000.

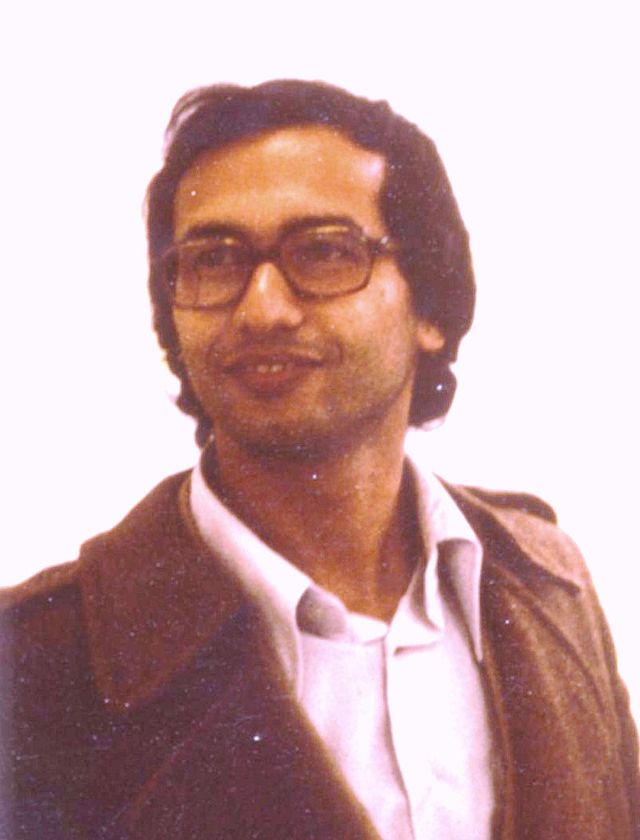

Djaout graduates in 1976 and goes on to work as a journalist for the French language newspaper Algerie-Actualite. While working as a reporter he had four novels published: L’Exproprie (1981), Les Chercheurs d’os (1984), L’Invention du desert (1987), and Les Vigiletes (1991), the last of which was awarded the 1991 Prix Mediterranee literary award in France. Running themes in his novels were a cry against despotism and a call for respect for human rights. In January 1993 Djaout co-founded the weekly newspaper Ruptures.

Tahar Djaout, editor-in-chief of Algérie-Actualité, was one of the outstanding Algerian Francophone writers of his generation. He began his literary career as a poet in the Seventies before making his mark as a writer of fiction in the Eighties. His four novels and a collection of short stories, published between 1981 and 1991, provide sensitive depictions of contemporary Algerian society.

Much like his character Boualem in the book, he dreamed of a better society:

In the oppressive city where he used to live and still lives, Boualem Yekker had put together dreams- oh, he no longer dares to do so-about the ideal city where he would like to live and watch his children blossom. First, there would be greenery trees and lawns-much greenery that would provide shade, coolness, fruits, the music of leaves, and shelter for love. There would be creators of beauty, rhythms, idylls, buildings, and machines. But there was no place at all for coordinators of the faith, supervisors of conscience, guardians of morality, and those establishing the power of Heaven. Boualem Yekker yearned for a humanity liberated from the terror of death and eternal punishment. But his dreams had failed to come true.”

He knows for the dream to come true, we need the words. Words that are quietly laid in the books and are patiently waiting to be read. The real words, the dangerous words, and not the ornamental words. Albert Camus once said: “To create today is to create dangerously.” Like Camus, Tahar Djaout also believes in the power of words:

“For words, put end to end, bring doubt and change.”

Therefore, the mission of the oppressor is to burn the words. Make them vanish.

“By now they have no doubt burned all his books in an exorcizing fire. They understand the danger in words, all the words they cannot manage to domesticate and anesthetize.”

Tahar Djaout was the voice that they needed to suppress. He believed:

“Silence is death, and you, if you talk, you die, and if you remain silent, you die. So, speak out and die.”

But Boualem Yekker, the character in the novel is different. As Tahar Djaout writes in his book, he is a humble reader and he realizes that he will not be the creator, but can only be the keeper:

Boualem Yekker is not that poet. He is only a humble dreamer who has not been visited by poetry Of course… But Boualem did not live with the illusion for long; he quickly realized that others had created the books he could not create…Boualem became instead a reader and a salesman of the jewels that his mind and hands had proven incapable of crafting. He did so without joy in his heart; suddenly accepting his own death, he understood that nothing of himself would remain beyond his disappearance. Boualem accepted dying.

Boualem thinks:

Perhaps he will be a writer in another life? It is true that a single lifetime is too short to accomplish all that you want. There are so many deformities you would like to correct, so many events you would like to approach from another angle, so many trails you would like to cover over, so many wounds or affronts you would like to erase: at least one other life is needed to do this.

Reading these lines, one cannot help but ponder that Tahar Djaout’s time finished too soon, and one lifetime was certainly not enough for him. As a creative soul, unlike Boualem, he would have not easily accepted his death. He would have wished for another lifetime, preferably one with another spring.

Tahar Djaout 1954-1993

*If you’re interested in a comprehensive and in-depth review of the Last Summer of Reason, I highly recommend The Exiled Soul blog post, which you can find here: