I left a land that wasn’t mine

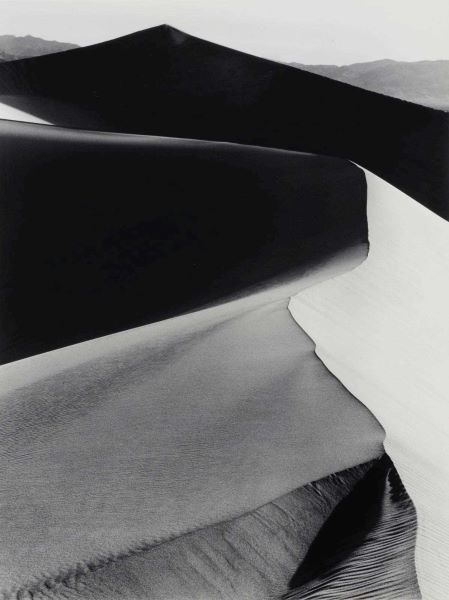

- Ansel Admas, Sand Dunes, Sunrise, Death Valley, California, 1948

I left a land that wasn’t mine,

for another that’s not mine either.

I sought refuge in inked words, in books I had a place,

a word from nowhere, from the darkness of the desert.

I did not cover myself at night.

I did not shield myself from the sun.

I walked naked.

Where I came from had no more meaning.

Where I was going didn’t worry anyone.

Wind, I tell you, just wind.

And a little dust in the wind.

This poem by Edmund Jabès has captivated me for some time now. It lives in my head. Its beauty is painful. Its words will linger on. I was initially introduced to this poem through a remarkable translation from French to Persian, courtesy of the talented writer and editor, Parham Shahrjerdi. On occasions, I have shared this poem with friends, and I have noticed that they immediately connected to it, particularly ones that left their homeland.

The Poet and writer, Edmund Jabès was forced to leave his homeland too. He was from a French-speaking Jewish family. In 1956, after the Suez Crisis, Jabès was forced to leave Egypt due to the rise of anti-Semitic sentiments and moved to France. It was in Paris that his career truly flourished, and he became an influential figure in the French literary scene.

Jabès writes mostly from a perspective of exile. Although he was not a practicing Jew, he became curious about the Jewish identity after the exile and became a narrator of the Holocaust and the human condition. Jabès’ most significant work is the seven-volume “Book of Questions” (“Le Livre des Questions”), which he published between 1963 and 1973. This series of texts is a blend of poetry and philosophy. The books are known for their unique structure, which consists of a combination of aphorisms, poems, dialogues, and narratives, reflecting the dislocation and fragmentation experienced by those who leave their home.

What makes a piece of land your home? What makes you belong? If you live in a place most of your life, does that make it home? What if you die there?

Reza Barahani, an Iranian writer living in exile, in his will, asked to be buried in Iran after his death. For him, the idea of dying in a foreign land, one that is not yours, was somehow more painful than living in it. He thought, now that I couldn’t be in my homeland as a living person, my dead body is of no threat; it will lie there still and bother nobody. As it turns out, totalitarian regimes were afraid even of a dead body and denied his last wish. He died in a foreign land and where he came from had no more meaning and where he was going, didn’t worry anyone.

Edmund Jabès also leaves his homeland for another land that is not his, walking naked through the desert like the wind. What will you become when you leave your homeland? immigrant, exilé, refugee, expatriate? Amir Ahmadi Arian explores it in his deeply moving and heartfelt essay:“ Maybe English, the ultimate language of colonial settlers, can’t conceive of a word that could capture what people like me experience. So I went back to Persian, the other language I know, to see if that old tongue of fallen empires and sublime poets had a better name for me.” He then decides that “In Persian, there is a word, avareh (آواره), which doesn’t have an accurate equivalent in English.” He then quotes the great Iranian writer, Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi:

“Avareh doesn’t have a choice. He has to accept any shelter. He is in jail with great weather and tasty food and nice clothes. He is a stranger, dead inside, lost, tired, perplexed, alien, weak, angry, nervous, and quivering. His feet are at the edge of a well and he is constantly wondering why he hasn’t jumped yet […] Immigrant, by contrast, is hopeful. He thinks he has gotten over the shock. He smiles. He jokes. He develops his palate and his knowledge of colors. He takes vitamins to enhance the balance of his body, visits museums, goes to the movies, takes walks, wears ties, and whiles away in the parks. He thinks he has put down new roots, not knowing that even the sturdiest trees, once uprooted, are doomed to wither to death.”

Was Edmund Jabès an Avareh too? Is that what he means by dust in the wind? In his writing, Jabès often thinks of language as a form of exile, a place where words and meanings are constantly shifting and are elusive. Jabès believed that language is a site of both longing and loss, a place where we try to make sense of the world around us but are constantly confronted with the limitations and ambiguities of words.

In an interview that was first published in the Los Angeles Times (December 1, 1982) he says:

“Finally, little by little, I realized that the Jew not having had a real homeland for thousands of years, since obliged to leave one place for another each time, what did he do? He made the book his true home, his real territory… And I found that there was such a similarity between the Jew and the writer, that it struck me in an amazing manner… And little by little I told myself, Me too. Oh, I was at home in France, but it wasn’t my landscape. And for all that, the book was substituted. That is, I too made the book my place, my homeland, as if I could live only in the book.”

The great German poet Friedrich Rückert, in his melancholic and beautiful poem ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen,’ which was later set to music by Gustav Mahler, reminds us that despite all the failures and tragic events, we can take solace in art. ‘I am lost to the world…I live alone in my heaven/ in my loved one/ in my song.’ The song is one of Mahler’s most famous and beloved works, a deeply personal creation that reflects the composer’s own life and artistic vision. Rückert was also forced to flee his home in Coburg during the German Revolution of 1848-1849 and spent several years in self-imposed exile in Switzerland. During this time, he too like Jabès, wrote many poems that reflected his feelings of displacement, nostalgia for his homeland, and belonging.

Perhaps Edmund Jabès was not a complete Avareh. Perhaps we will always remain a little Avareh in our hearts. Or maybe if we are lucky, we will find a home in words. Our world is filled with captivating stories of people who adopted the new language and wrote their stories. They even add beauty to the newly inhabited language. Take Joseph Conrad, a Pole who made English his own and wrote many beautiful novels and is one of the most influential writers in English. Edmund Jabès is one of these people. He wrote for all the dislocated and displaced people on Earth so that for a moment we could forget the fleeting and impermanent nature of existence, like dust in the wind.