Reading Hisham Matar

Later in the talk, he shares his passion for Irish writers and how he thought in his youth that the soil of Ireland must be magical because it produced such brilliant writers: Beckett, Joyce, and Keats, and he pledged to himself that if he ever set foot in Ireland, he would kiss its soil before doing anything else. Years later, when he was invited to Ireland as a notable writer, getting off the plane, he remembers this old pledge. With shame and caution, he bends down to tie his shoelaces as an excuse and quickly kisses the finger that touches the ground. He shares this memory with Debra Treisman with a hint of humor and slight embarrassment, but one cannot enjoy the vulnerability he shows in his love for great literature. In the CBC podcast, Writers and Company, Eleanor Wachtel, introduces him as follows: “Hisham Matar was born in New York in 1970 to Libyan parents. His father was part of the Libyan mission to the United Nations at the time, but he resigned in 1973 when the dictator Muammar Gaddafi tore up the constitution and declared himself: “leader for life”. Hisham’s father’s resignation, a sign of independence, and resistance marked him in “Gaddafi’s regime”, and although the family returned to Tripoli, a few years later, they realized that they would be safer if they lived outside of Libya. Eventually, they managed to escape to Cairo. Hisham was sent to England for protection, (and studied there under a false name). He was seventeen in 1990 when he found out that his father was abducted by the Egyptian security forces and handed over to the Libyans. (Jaballah Matar) was tortured and imprisoned in Tripoli. After a couple of years, in 1995, he managed to send a letter in the form of a recorded tape to his family. This was the last time they heard from him directly. Reading Hisham Matar without being aware of this major event in his life is impossible. As the narrator in his book Anatomy of a Disappearance, says:“The things that I want as a greedy reader; I want ideas and emotions, but also, I want architecture and I want somebody who knows how to pace and construct something. I don’t think you can do all of those if you don’t have a kind of good manners, which I think gentleness is profoundly reliant on. Not the passive gentleness, but the act of gentleness to try to really see something with such complexity. To go around it, not with the intention to sort of rip it up and flatten it out and consign it to some kind of formula, but to go around it and look at it and then leave it at the end of the story like this one does, to leave it in such a way that maintains its resonance and you feel the resonance of the story sink much more paradoxically once you’ve left it a month later or something… I have such profound confidence in the human imagination and how it does that.”

“There has not been a day since his sudden and mysterious vanishing that I have not been searching for him, looking in the most unlikely places.”Hisham Matar, who was passionate about music and poetry, graduated from the University of London with a degree in architecture and worked in a design firm for a while, but after the publication of his first book, he became a full-time writer. His first book “In the Country of Men” was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Guardian First Book Award and several other international prizes. It has been translated into twenty-eight languages. The book is about a family who lives under the Gaddafi regime in 1970. The father is a serious opponent. The story is told from the point of view of a nine-year-old child, a boy named Suleiman, who witnesses the events of those years and tries to make sense of them. There is a surreal scene in this book about a public execution in a stadium, where the condemned is hanged in front of a large crowd of people and all of this is broadcast on national television. In a conversation with Sarah L’Estrange in 2015, Hisham Matar says: “I didn’t know I was the first one to write about these things. There was a shame in talking about it.” Journalist and author, Christopher Hitchens, wrote in his article “The Unmentionable Truth about Libya” published in Vanity Fair in 2011: “There has been little in the way of real political accountability or soul-searching over what happened in Libya, and indeed there has been a kind of omertà or conspiracy of silence about it. It’s as if a tacit agreement has been reached that it’s better not to discuss it or even allude to it.” In a session held at the Conduit Club in June 2019 recorded for “Libya Matters: Libya and the Forgotten Revolution”, he mentions:

Living under the dictatorship regime and how it infiltrates intimacies in our life is a subject he is very curious about and he often writes about it. In 2011, Hisham Matar’s second book, “Anatomy of a Disappearance” was published. Nuri, a teenage boy, falls in love with Mona—the woman his father will marry. Consumed with longing, Nuri wants to get his father out of the way and take his place in Mona’s heart. But when his father disappears, Nuri regrets what he wished for. Alone, he and Mona search desperately for the man they both love, only for Nuri to discover a silence he cannot break and unimaginable secrets his father never wanted him to know. The father’s disappearance remains a prominent theme in the book, with the protagonist being a teenager on the verge of adulthood. But the book is more than just a coming-of-age story. With prose that seems more beautiful and poetic than his first novel, Hisham, tells a story about longing and loss, and love. The novel explores the relationship between mystery and intimacy. Intimacy is the center of this story between the father and son. Something in the grandeur of a Greek tragedy with a touch of mystery fiction makes the story even more captivating. In 2012, he returned to Libya with his mother and wife to find some traces of his father, and the novel ‘The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between’ is the result of the memories of this journey. The book is beautifully written and very emotional. It bravely and delicately explores all the feelings that arise when one returns after a long time to a place they once knew. All the hopes and fears. His confrontation with Libya, a country he had tried hard to forget, and his fear of finding the truth about his father’s fate, which he had been waiting for all these years. The historical truths about Libya and the life of people during Gaddafi’s regime are hard to read, but at the same time, it is incredible that we get to read about these unusual events, like the encounters with his family members who were imprisoned in Libya and how people are living their lives now in the aftermath of a dictatorship. There is this moment about the Libyan revolution in 2011 in the book. The night when a group of lawyers of the political prisoners and former judges gathered in front of the Benghazi courthouse to protest. “Although they considered it a symbolic move and expected a severe crackdown, instead they were faced with hundreds of families of the deceased who joined them. Revolutions have their momentum, and once you join the current it is very difficult to escape the rapids. Revolutions are not solid gates through which nations pass but a force comparable to a storm that sweeps all before it.” This memoir goes beyond the search for a disappeared father and beautifully explores the human condition in exile, life in a foreign language, and finding one’s place in the world.“Libyan perhaps not unlike others, maybe a little bit more than others, I like to think, are not particularly good at engaging with the traumas of their history. We have very particular drama in Libya because you have the Italian colonial experience which was very violent. Italy, to subdue the resistance killed 45% of the population of Cyrenaica, a fact that is so little known in the world. We have so much anguish from the past, then we had the Ghaddafi experience and the public executions of the 1980s. People were left hanging in the streets until their bodies rotted and that was, according to the dictatorship, a sign of their ill character, and the traffic was diverted so as you drove by those bodies. All that is so difficult to talk about. So, people don’t talk about these things for obvious reasons. All countries are susceptible to national psychosis, and we’ve had a share of that.”

“Exile is more than a geographical concept, it is a psychological state: a condition of estrangement from ourselves and others.”In the Fresh Air radio with Terry Gross in 2007, he says: “One of the strangest notions about exile may be that the place you leave will remain the same, just as you will remain unchanged, and of course, neither is true. The place changes, and you too change over time and find a new identity.” Going back to Libya after thirty-three years brings all the doubts and emotions about exile and return:

In 2017, ‘The Return’ won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography and has since been translated into several languages, including Persian. When reading his memoir, it’s hard not to ask oneself: How did someone endure such pain? Hisham Matar speaks of an old habit he had when he was nineteen and twenty years old, living alone in London. During those tumultuous times when he found out about his father being abducted, he would go to the National Museum of London every day to see paintings. However, he soon realized that he couldn’t move from one painting to another like everyone else. Instead, he would choose a work of art and spend some time in front of it each day. It usually took him a month to move on to the next work of art. It was during these years that he became acquainted with the Sienese school of paintings:“The plane was going to cross that gulf. Surely such journeys were reckless. This one could rob me of a skill that I have worked hard to cultivate: how to live away from places and people I love. Joseph Brodsky was right. So were Nabokov and Conrad. They were artists who never returned. Each had tried, in his own way, to cure himself of his country. What you have left behind has dissolved. Return and you will face the absence or the defacement of what you treasured. But Dmitri Shostakovich and Boris Pasternak and Naguib Mahfouz were also right: never leave the homeland. Leave and your connections to the source will be severed. You will be like a dead trunk, hard and hollow. What do you do when you cannot leave and cannot return?”

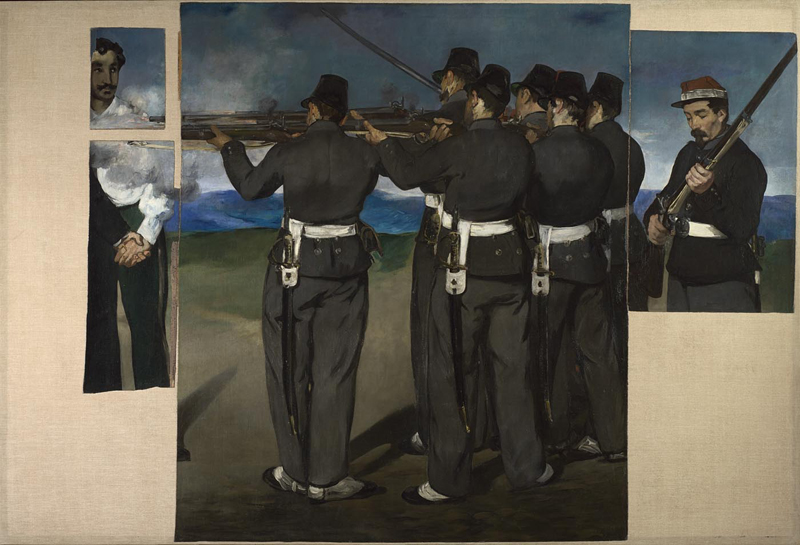

After writing the book return, Hisham Matar thinks it’s time to take his pleasure seriously and he believes it’s time for him to visit the city he admired for so long from afar: Siena.“One of the ways that I moved around the National Gallery is that I would have a target. I was interested in Velázquez, Manet, and Cézanne — painters that, although mighty and distant, felt somehow reachable to me. I had some tools to connect to these people and to engage with their work, rightly or wrongly. But with the Sienese School of painting, which was in a different wing… there was something about those paintings that I felt was very distant from me. It felt that they came from a faraway tradition and had a purpose to remind the faithful, to be part of their worship. But these Sienese paintings particularly got me in a way that I didn’t quite understand. I kept returning to them and looking at them.”